Saturday, December 12, 2009

THE ISLANDS HAVE A MUCH DEEPER HISTORY

THE LIGHT OF ANDAMANS, Vol 34, Issue 20, December 11, 2009

http://www.lightofandaman.com/news5.asp

The recent call by the All India Forward Block (The Light of Andamans, Nov. 25, 2009) to rename the Andaman & Nicobar Islands as Shaheed and Swaraj is neither new nor unexpected. It has been around in the islands since the 1950s and more recently even others like historian Swati Dasgupta, for instance, have made the same call (‘Remembering Kaalapani’, The Times of India, May 7, 2005)

If these calls are heeded, these islands could well see a monumental shift in their present namescape. The island named after Sir Hugh Rose, the man who finally cornered Rani Laxmibai of Jhansi after the mutiny of 1857, could soon be named Laxmibai Dweep or maybe Rani Jhansi Dweep. Havelock Island named after the British General who re-took Lucknow from Nana Sahib could well be named Nana Sahib Dweep and the direct reference to the call by Subhas Chandra Bose is the most evoked one in any case.

The Rani of Jhansi or Nana Sahib may have known little of the islands (or even that they existed) but that surely is of little consequence.

This group of 500 odd islands scattered in an arc in the Bay of Bengal, are certainly fertile territory for a massive, even lip smacking renaming exercise – Tantya Tope, Mangal Pandey, Subhas Chandra Bose, Veer Savarkar…how about Mahatma Gandhi, Pandit Nehru, Rajiv Gandhi….the list is endless; one’s imagination the only limitation and why not – reclamation of one’s history, after all, is believed to be one of the most important and effective tools of nation building.

There is one hitch however, a question that renaming enthusiasts might want to first consider – How does one reclaim what was never yours in the first place? The islands, located far away from mainland India can only be considered a gift that British left India with when the empire disintegrated. There are undeniable connections of India’s freedom movement with the islands; best symbolized by the mutiny of 1857 and the Cellular Jail. There can be no denying that and neither can one deny the close bonds that a large section of the country feels with these islands, but, and this is the crux of the argument here, all put together this history does not go beyond a 150 years. We might want to rename Havelock Island in the memory of Nana Sahib, but is it not worth asking whether the island that is today called Havelock had some earlier name too?

Let it not be forgotten, the Andaman and Nicobar Islands have been the traditional home of a number of aboriginal communities - the Great Andamanese, Jarawa, Onge and Sentinelese (in the Andamans), the Nicobaris and the Shompen (in the Nicobars) that have been living here for nearly 50,000 years. The 150 years that we want to claim now is like the blink of an eye in comparison. Injustices have been done and continue to be done to these communities in a manner that has few parallels in India. Their lands have been taken, their forests converted to plywood and agricultural plantations, and the fabric of their societies so violently torn apart that extinction looms on the horizon for many of them. The Great Andamanese who were at least 5000 individuals when the 1857 mutiny happened are today less than 40 people. The Onge who were counted at about 600 individuals in 1901 census are only a 100 people today. There are critical issues of survival that these communities are faced with – problems that are complex and will be difficult to resolve. If indeed there is energy and interest in doing something in the islands and for the islanders these are lines that we need to be thinking on.

These are people, like indigenous peoples everywhere, who have their own histories, their own societies, and yes, their own names for the islands and places. First the British called something else and now we want to call something else again. If indeed the places have to be renamed, should not an effort first be made to find out what the original people had first named them, why they were so named, what the significances were and which names are still in use by them. Should that not be the work of scholarship and historical studies? Why is that this is not a history that political parties want to correct? It would be a far more challenging and worthwhile exercise and perhaps not a very difficult one either because a lot of information does already exist.

If indeed the real and complete history of the islands is ever written, the British would not be more than a page and India could only be a paragraph. How’s that for a perspective and a context?

*Pankaj Sekhsaria is the author of Troubled Islands – Writings on the indigenous peoples and environment of the Andaman & Nicobar Islands

Friday, November 27, 2009

Protected Area Update - December 2009

If you want any specific stories or the entire update as an attachment, please write to me at psekhsaria@gmail.com

Pankaj Sekhsaria

Editor, 'Protected Area Update'

C/o Kalpavriksh

---

News and Information from protected areas in India and South Asia

Vol. XV No. 6, December 2009 (No.82)

---

LIST OF CONTENTS

EDITORIAL

The day of the dolphin

NEWS FROM INDIAN STATES

ANDAMAN & NICOBAR ISLANDS

ZSI survey in islands of Rani Jhansi Marine NP

ASSAM

Tourism infrastructure enhanced at Pobitara Wildlife Sanctuary

Spate of wildlife deaths in and around Kaziranga National Park

Human-elephant conflict takes heavy toll along Assam - Bhutan border

Human-elephant conflict takes heavy toll along Assam - Bhutan borderAwards given to Assam FD personnel

Joint committees to monitor transmission lines for elephant safety

Two rhino poachers killed in gun battle in Rajiv Gandhi (Orang) NP

BIHAR

Special efforts to prevent dolphin hunting

GUJARAT

1550 trees to be cut over seven acres of land adjoining Gir WLS

Maldharis insist on living in Gir; memorandum given to President

KERALA

38 casualties in boat tragedy in Periyar TR

‘Orientation Programme on Wildlife Conservation’ for Kerala High Court judges

MAHARASHTRA

Opposition to religious gathering within Bhimashankar WLS

Trees over 50 hectares to be cut in the Great Indian Bustard WLS

Conservation Reserve status proposed for Mahendri Reserve Forest

Conservation Reserve status proposed for Mahendri Reserve ForestMEGHALAYA

Community reserve for pitcher plant conservation in South Garo Hills

NAGALAND

Singphan RF declared as Singphan WLS

ORISSA

Oil spill concerns for Gahirmatha

SC notice against Dhamra port

Orissa to constitute State Wetland Management Authority; Integrated -Management Plan for Chilika Lake

Orissa to constitute State Wetland Management Authority; Integrated -Management Plan for Chilika LakeOrissa may take the help of traditional elephant catchers from Assam to mitigate man-elephant conflict

RAJASTHAN

Rs 104 crores for relocation of villages from Ranthambhore TR

Great Indian Bustard sighted in Barmer part of Desert NP after 25 years

TAMIL NADU

MoEF says no to neutrino project proposed in Nilgiri BR

UTTAR PRADESH

UP plans to protect Gangetic Dolphin

2nd phase of rhino introduction planned in Dudhwa TR

WEST BENGAL

Concrete embankments proposed to protect Sunderbans

Two rhinos deaths in Jaldapara WLS; elephant safari stopped

NATIONAL NEWS FROM INDIA

Gangetic Dolphin is National Aquatic Animal

Centre approves cheetah reintroduction roadmap preparation

Ecotone – New newsletter on wildlife and conservation in North East India

Endangered species list under the Biological Diversity Act

National Tiger Conservation Authority reconstituted

NTCA to issue identity cards for tigers; also to use new tool ‘payment of ecosystem services’ for conservation

Zoological Survey of India activities related to protected areas

SOUTH ASIA

NEPAL

Nepal Army gears up for anti-poaching drive

INTERNATIONAL NEWS

Tiger population falls in Myanmar’s Hukuang Tiger Reserve

OPPORTUNITIES

CEPF Call for Proposals for Western Ghats

PROTECTED AREAS IN THE COUNTRY: LATEST NUMBERS

AWARDEES - CMS VATAVARAN ENVIRONMENTAL FILM FESTIVAL - 2009

UPCOMING

National meeting of the Association for Tropical Biology and Conservation (ATBC)

IN THE SUPREME COURT

--------

THE DAY OF THE DOLPHIN

It is ironic that a civilisation that is so dependant, indeed nourished by its rivers is so callous to their plight today. There is hardly any river in the country now, whose natural flow has not been altered by dams and barrages or which has not become a carrier of our municipal and industrial waste. The waters that have been the source of life and nourishment for centuries are, now, almost dead themselves. Needless to say, the fate of the dolphins and a multitude of plant and animal life that depends on these systems is fated to meet the same end. That they are not seen often has not helped matters worse. ‘Out of sight’, in this case, has clearly been a case of ‘out of mind’.

Little, for instance, is known of the biology or even the number of the Gangetic dolphins that survive today. The most optimistic estimates put their number at about 2000, spread over rivers in the Gangetic basin and in the Brahmaputra river system.

The new status of the animal will hopefully change the present situation and if some reports in this issue of the Protected Area Update are some indication, this is already beginning to happen. The states of Bihar and Uttar Pradesh have almost immediately expressed their intentions (and in some case also taken steps) for dolphin protection and conservation. A further interest in the dolphin has also been spurred in Assam, where the creature has already been the state aquatic animal for over a year now.

What will be crucial is how the intentions are operationalised on the ground, or for that matter in the water. It needs to be borne in mind that some ‘band-aid’ kind of suggestions and solutions (arrest fisherfolk, awareness programs in schools etc) alone will simply not work. The status and fate of our rivers are symptomatic of deep and underlying problems with our development process where damming of rivers, chemicalisation of our agriculture, rapid industrialization and urbanization have been given priority over everything else. More than 168 large dams, for instance, have been planned in the Brahmaputra river basin alone, with little realization that this will change the entire ecological system and adversely impact the dolphin. It is precisely these kinds of developments that are working as a noose around our rivers and the diverse life found in them.

If the dolphin must have it’s day, it is this process that needs a fundamental and serious re-engagement and re-structuring; otherwise declarations that accord national status will amount to nothing more than symbolic lip service. And that as well all know, is not going to achieve anything at all.

---

Protected Area Update

Vol. XV, No. 6, December 2009 (No. 82)

Editor: Pankaj Sekhsaria

Editorial Assistance: Reshma Jathar

Illustrations: Madhuvanti Anantharajan

Produced by: Kalpavriksh

Ideas, comments, news and information may please be sent to the editorial address:

KALPAVRIKSH

Apartment 5, Shri Dutta Krupa, 908 Deccan Gymkhana, Pune 411004, Maharashtra, India.

Tel/Fax: 020 – 25654239.

Email: psekhsaria@gmail.com

Website: www.kalpavriksh.org

---

PUBLICATION OF THE PA Update has been supported by

-Foundation for Ecological Security (FES)

http://fes.org.in/

-Duleep Mathai Nature Conservation Trust

C/o FES

-Greenpeace India

www.greenpeace.org/india/

-Royal Society for the Protection of Birds

www.rspb.org.uk/

-Indian Bird Conservation Network

http://www.ibcn.in/

---

Information has been sourced from different newspapers and the following websites

http://wildlifewatch.in/

http://www.cmsindia.org/cms/sector/cmsenvis.html

http://indiaenvironmentportal.org.in

Monday, November 9, 2009

Day of the Jackals

Nature meets nurture in a startling and ancient ritual in the black hills of Kutch.

OUTLOOK TRAVELLER, November 2009

http://travel.outlookindia.com/article.aspx?262645

by Pankaj Sekhsaria

The jackals at their cement dining table feed on jaggery-sweetened rice (Pic: Pankaj Sekhsaria)

Located at the very edge of the beautiful and diverse land of Kutch, like sentinels rising high and keeping watch over the haunting landscape, are the Black Hills of Kutch, also known as Kala Dungar. At about 1,500ft, this is also perhaps one of the best places to get a bird’s eye view of the extensive and seemingly endless expanse of the Great Rann of Kutch. For while the Great Rann may be one of the most inhospitable and harsh environments on this planet, from atop Kala Dungar it seems anything but that. What meets the eye is a stunning vista of endless white that extends to the horizon and beyond; white that constantly changes shades with the changing light and moving clouds; white that is sometimes tinged the lightest of pink, then grey and then white again.

“There is no beginning and no end,” Lakshman, our driver and guide, starts off just on his own. Lakhubhai, as he is better known, talks of the creation of the universe, “Brahmand Rachna,” he says, “This is how the universe must have been created—where land merges with the Rann, the Rann with the ocean and the ocean with the horizon, all different and yet seamlessly one thing.”

Views of the Great Rann from atop Kala Dungar (Pic: Pankaj Sekhsaria)

But continuing along these profound lines would be getting away from the point. It was not the Rann that we had driven to the top of Kala Dungar for. The Rann was only a side show, the main attraction being a daily event here that sounded both bizarre and fascinating when I first heard about it. At the very top of Kala Dungar is an old and much venerated temple of Guru Dattatreya where the wild jackals of the mountainsides are fed sweetened rice every day.

Nobody knows the exact origins of this strange phenomenon, but the most popular legend is related to the compassion of a holy man. According to common folklore the priests here regularly offered food to the jackals. A time came when there was no food to offer and this is when the Pir of Pachchmai, also known as Guru Dattatreya, offered a part of his body to the animals. The tradition of feeding the jackals continues and rice sweetened with jaggery is offered to them twice every day—first around noon and then just a little before dusk. Earlier it was a human call of “le ang, le ang (take my body)” that summoned the jackals; today it is the ringing of the bell that indicates to them that food is on its way—a perfect Pavlovian experiment in the wild.

An important sign on the way (Pic: Pankaj Sekhsaria)

It is nearing noon and we rush back to the site near the temple where the jackals come to feed. A circular cement platform, about a metre high and three metres across, serves as the dining table for the jackals. The animals are clearly aware and expectant. They emerge tentatively from the scrub forest, running around nervously in ones and twos and then disappearing back into the bushes. But their sense of anticipation is high and evident.

Then the bell starts ringing and a man wearing a white shirt with a simple metal container on his head walks the roughly hundred metres to where the jackals will get their feed. A couple of jackals are trailing him now and more emerge as he stands by the platform, lowers the container and throws out handfuls of the rice.

Harjibhai, the jackal feeder (Pic: Pankaj Sekhsaria)

There is no restraining them now and in just a moment at least 20 are on top of the platform grabbing every morsel that they possibly can. Some stand and eat, others growl and snatch and still others jump up, snatch a bite and quickly slink away. A couple of persistent crows join the 30-odd jackals in a feast that’s over in less than 10 minutes. The jackals are gone as quickly as they came and the crumbs that remain are now being cleared by an opportunistic mongoose and a couple of stray dogs that have been waiting their chance. It is just another day in the life of the temple authorities, the jackals, the dogs, crows and the mongoose; but for a one-time visitor like me, it is unlike any other day or event I have seen before.

I’m keen to find out a little more and go in search of a saffron-clad swamiji I’d seen on the way up. He seems to be a little high on dope and is not in the least pleased at being disturbed. “Go and meet Harjibhai,” he tells me, “he’ll tell you.” Harjibhai is indeed the right man—the man in the white shirt whose job it is to cook the rice for the jackals and then carry it to them after the bell is rung. He knows little himself, but fills me in with some interesting nuggets.

Fossils, on the way (Pic: Pankaj Sekhsaria)

He’s been doing this job for three years now and the grain is provided for by a village at the foothills. Every meal for the jackals is eight kilograms of rice cooked with four kilograms of jaggery. He recounts the legend again and then adds a fascinating detail. There are rare occasions, he tells me, when the jackals refuse to accept the offerings made to them. It is an indication that some wrongdoing has occurred in the villages below and that some corrective action is needed. This, he further confirms, is exactly how the situation turns out to be.

Hard to swallow? But then who would have believed that a hilltop exists in a remote corner of Kutch where jackals have been fed sweetened rice since time immemorial.http://3fotosaday.blogspot.com/2009/11/jackals-of-kala-dungar-kutch.html

http://3fotosaday.blogspot.com/2009/11/jackals-of-kala-dungar-2.html

http://3fotosaday.blogspot.com/2009/11/kala-dungar-kutch-3.html

Monday, November 2, 2009

On the Edible nest swiftlet...

by Pankaj Sekhsaria

Indian Birds, Vol. 5 No. 4 July–August 2009

Date of publication: 15th October 2009

www.indianbirds.in

PROLOGUE: This piece was first written sometime back, in 2004, and with detailed inputs from discussions with Dr. Ravi Sankaran himself. Tragically, Dr. Sankaran passed away in January 2009, after suffering a massive heart attack.

In a very recent development it was reported in August (Selling bird’s nest soup to save this bird: there’s a change in law, Tuesday, Aug 18, 2009 at 0354 hrs New Delhi: http://www.indianexpress.com/news/selling-birds-nest-soup-to-save-this-bird-theres-a-change-in-law/503342/0) that the Edible nest swiftlet had indeed been de-listed raising hopes that the project he had initiated in the Andamans will get a fair chance of being implemented and being successful.

---

The path to hell, for humans, it is said, is paved with good intentions. For a little bird in the Andaman & Nicobar Islands, the Edible-nest Swiftlet Collacalia fuciphaga, the path to extinction, it would seem, too has being paved with similar good intentions. Being listed in Schedule I of the Indian Wildlife (Protection) Act, 1972 (WLPA), is the ultimate recognition of the endangered status of any creature in India

A NEST OF SALIVA

It also means that the highest degree of protection will be accorded to the species, and this is exactly what has happened in the case of the Edible-nest Swiftlet too. Herein lies the ultimate paradox, and probably the seeds of an unfolding tragedy. At the crux of the matter is the nest of the bird that is made entirely of its own saliva. The final product is a beautiful white ‘half-cup’, roughly six centimeters across with an average weight of 10 gm.

This is indeed a fascinating biological quirk, but one for which the bird has had to pay a heavy price. Since the 16th century, when the nest of the bird is reported to have become an important part of Chinese cuisine and pharmacy, its been heavily exploited across its range. While there is little modern scientific evaluation or validation of the efficacy or efficiency of the nest, consumption has been immense. A TRAFFIC International publication of 1994 estimated that about nine million nests, weighing nearly 76 tonnes, were being imported into China annually. Not surprisingly then, the wholly edible white nest was and continues to be one of the world’s most expensive animal products, pegged sometime back at US $ 2,620¬4,060 per kg in retail markets in the South–east Asian countries.

It is well known that a part of the international trade was being fed by the extraction of nests that takes place from the Andaman & Nicobar Islands, but authentic information only started coming in 1995, when the first studies were initiated by ornithologist, Dr. Ravi Sankaran, of the Salim Ali Centre for Ornithology and Natural History (SACON). He initiated a laborious and painstaking process of locating the nesting sites and enumerating the nests and birds. Detailed surveys were conducted on the islands between March 1995 and early 1997, where he visited a total of 385 caves (325 in the Andamans). The outcome was two pioneering reports. The first published in 1995 dealt with the Nicobars and the second, in 1998, presented a complete picture of the situation in the entire archipelago.

A THREATENED POPULATION

Sankaran’s studies estimated that the total breeding population on the islands was about 6,700 breeding pairs. He reported that at least 94% of the caves were being exploited for the bird’s nest, and that less than 1% of the breeding population was being allowed to successfully fledge as the nests were being harvested for the market before the nesting could be completed. Sankaran estimated that the Edible-nest Swiftlet had experienced a whopping 80% decline in its population, placing it in the critically threatened category (IUCN criteria A1c). This was primarily due to indiscriminate and unrestricted nest collection from the wild, leading him to the further conclusion that if this was not dealt with urgently the bird would soon be extinct in the Andaman & Nicobar Islands.

He initially advocated strict protection, but changed his stand when he realised that protection, in the conventional sense, would not work. He also learnt of the ingenious house ranching methods developed by the Indonesians for managing swiftlets.

HOUSE RANCHING

It was estimated that nearly 65,000 kg of nests were being produced in Indonesia annually, from colonies of the Edible-nest Swiftlet that reside within human habitation: a total of 5.5 million birds and their nests, in houses and rooms of human habitations, optimally managed by humans. “Thus, while swiftlet populations in caves will continue to decline, or become extinct, due to collection pressures,” Sankaran concluded, “the species will survive because there are hundreds of thousands of birds that reside within human habitation, all optimally managed”.

Nest collectors, he started to advocate, would have to be empowered to harvest nests within the rigid framework of strictly scientifically harvesting regimes. This would have to be complimented in the ‘Indonesian way’, with a realistic long-term strategy that would include both in-situ and ex-situ conservation programmes, i.e., house ranching, both based on the economic importance of the species and using this importance to organise local communities to conserve the species.

In 1999, his recommendation took the form of an innovative initiative that was launched jointly by the Wildlife Circle of the Department of Environment and Forests, Andaman and Nicobar Islands, and SACON. The final aim of the initiative was to ensure protection of the nests in the wild so that eggs would be available for the house ranching ex situ component. The project took off well. Protection accorded to a complex of 28 caves on Challis Ek in North Andaman Island, and one cave on Interview Island Wildlife Sanctuary, saw over 3,000 chicks being fledged, a growth of over 25% in the population of the swiftlets at these sites. A team of local people, who were earlier nest collectors, were now being motivated towards protection, and subsequently, sustainable harvesting.

THE LAW BECOMES THE HURDLE

Just as phase one was taking off, the law came into the picture, and in October 2003 the Edible-nest Swiftlet was put onto Schedule I of the Wildlife Act. This meant that there could be no activity that involved use of, or trade in the nest of the bird—the primary premise on which Sankaran’s initiative had been based. The entire project was dealt a set back and in spite of continued efforts, over the years, to have the swiftlet removed from Schedule I, it continues to be listed there.

Admittedly there are genuine concerns about the de-listing of a species and the implications of an act of this kind. The biggest fear is of setting a precedent that could be misused by vested interests. In this case however, the recommendations are based on solid, detailed, and pioneering scientific studies of nearly a decade, and were in turn backed with a wealth of international information and experience. “Its more like apiculture,” would be Sankaran’s argument, “where bees are reared for their honey. House ranching of swiftlets cannot be likened to the farming of animals for skin or meat”. The implication of not delisting the bird is that the conservation initiative is bound to fail, while harvesting from the wild would continue unabated. The consequences of this would be the local extinction of the bird in the Andaman & Nicobar Islands—a predicament that was summed up with stunning simplicity by J. C. Daniel of the Bombay Natural History Society. Speaking during the concluding session of the International Seminar to commemorate the centenary Journal of the Bombay Natural History Society in Mumbai in November 2003, he spoke of the fate of the Edible-nest Swiflet if corrective action was not taken at the earliest: extinction by protection—the ultimate oxymoron.

---

You can also visit the following links for pictures of avifauna of the islands including the nest and the habitat of the edible nest swiftlet and Ravi in the field in the islands

http://3fotosaday.blogspot.com/2009/11/birds-of-a-islands-1.html

http://pankaj-atcrossroads.blogspot.com/2009/03/blog-post.html

http://pankaj-atcrossroads.blogspot.com/2009/01/remembering-ravi-sankaran.html

http://pankaj-atcrossroads.blogspot.com/2007/08/tilt-and-turmoil-in-andamans.html

Sunday, November 1, 2009

Wildlife is on the brink...

http://www.hindu.com/mag/2009/11/01/stories/2009110150170500.htm

CONSERVATION

Wildlife is on the brink…

PANKAJ SEKHSARIA

| … and it is high time we took a critical look at our conservation realities and policies. |

Most that share landscapes with wildlife, for instance, live extremely low impact lives yet they pay the biggest cost for conservation.

Question of survival: Tribal settlements in Orissa’s Simlipal Biosphere Reserve.

If there is one dominating sense about the fate of wildlife in this country, it is that of ‘the end’. The wiping out of the tiger from the Sariska and Panna Tiger Reserves has been headline news; poaching and trading in wildlife parts con tinues unabated; human wildlife conflict — be it with carnivores like leopards or tigers, large mammals like elephants or smaller animals like wild boar, deer or monkeys — is seriously on the rise; lakes, rivers and other wetlands are either being dammed, poisoned or encroached upon; climate change threatens to change the world in an unprecedented manner and as a combined consequence wildlife numbers are dwindling precariously and many species of birds, animals and plants stand dangerously close to the precipice of extinction.

The Forest Rights Act

An important new twist was added to wildlife conservation debates a couple of years ago with the enactment of the Scheduled Tribes and Other Traditional Forest Dwellers (Recognition of Forest Rights) Act, popularly known as the Forest Rights Act (FRA). The debate over this act has been volatile and the opposition, particularly from a section of wildlife conservationists and former forest officers, has been and continues to be strong. A lot has been written about these concerns and strong affirmation came from a rather unlikely source around a year ago. A report in Newsweek (“India’s missing tigers”, May 5, 2008) took the argument to an unexpected extreme when it argued that ‘democracy and economic development’ were driving the tiger to extinction in India.

Many might actually agree with this articulation, but even a cursory analysis will reveal that the conclusions are as ill-informed as they are short sighted. An entire argument cannot be built on the analysis of and comment on just one piece of recent legislation in the country: the FRA. The law is a recent one and its implementation, if it is happening at all, has just about begun. While fears about forest and wildlife loss may indeed be justified, selectively wiping away history and placing the responsibility for the tiger’s demise at the door of this one legislation and one set of people is not only irresponsible but also can be counter-productive.

Particularly so since because one aspect of India’s conservation history — the role of former Prime Minister Indira Gandhi — continues to be repeatedly invoked, like in the Newsweek piece. A whole generation of wildlife enthusiasts and conservationists believe, and with good reason, that Indira Gandhi ensured that Indian wildlife still has some hope. She was the architect of critical legislations and frameworks that certainly helped protect wildlife and her personal interest and intervention like in the case of Silent Valley in Kerala ensured that many critical habitats were saved.

It is a legacy we cannot deny or wish away, but we also need to ask whether we can keep hanging on to the past? Our socio-political-economic-cultural realities have changed drastically since her time. It is the same nation and yet it is different . Wildlife conservation today, like anything else, has to be placed within this rapidly changing context. It is crucial to recognise that the same wildlife conservation policies will not succeed today just because they did in a different era. If she were alive today, Mrs. Gandhi would perhaps have agreed.

There is also a whole new ‘post-Indira Gandhi’ generation of wildlife biologists involved in cutting edge research across wild India. Many of their formulations of problems and solutions are extremely nuanced and far more representative of realities on the ground. They need to be asked and they need to be listened to.

Condemning the most vulnerable

It is no one’s case that wildlife conservation is easy. The challenges are immense and no one but the most optimistic will argue that the future for our wildlife is bright and hopeful. However, blaming the poor and the tribal; demanding their displacement to protect wildlife; seeking stricter and military-like protection is the wrong place to start. By doing this we are also ignoring many other realities. Most of the communities that share landscapes with wildlife, for instance, live extremely low impact lives and yet they are made to pay the biggest cost for conservation.

It is also not a coincidence that innumerable people’s agitations across the country today are fighting policies and projects (big dams, large scale mining, increased industrialisation) that predate on the basic survival of forest and land dependant communities. Neither is it a coincidence that many of these are important habitats that support a great diversity of threatened flora and fauna. It is as important that we recognise this overlap as it is for us to recognise that both communities and wildlife are, together, losing this battle. Nothing — be it the laws and the courts, the politicians and the bureaucrats or the media and the wildlife conservationists — are able to help them.

Hope and the FRA

Increased mining across the country, for instance, has been one of the most significant sources of concern for its impact on forests, tribal communities and important wildlife populations. In an ironic twist now, it is being suggested that the FRA might actually be the only hope for preventing mining in forest and wildlife rich areas. Efforts towards this end are already being made in states like Orissa and in particular in the Niyamgiri hills where the Dongaria Kondh Tribal community itself is fighting to save the forests. Additional hope has been kindled following the July 30, 2009 notification of the MoEF stating the forest land diversion for non-forest purposes should ensure compliance with the provisions of the FRA.

In this larger context then, it comes across as completely unfair to argue that rights for the poor, the marginalised and the historically dis-privileged necessarily means the demise of our wildlife? Can we turn the question and wonder if, in fact, “it is not too much democracy but too little of it that lies at the root our wildlife crisis?” That a more empowered people might actually fight better and more successfully? We don’t have the answers today; what we do have is the choice of which question we will ask.

Bauxite prospecting pits on the Galikonda plateau in the Ananthgiri Hills of Andhra Pradesh. Mining is one of the biggest threats to tribal communities, forests and wildlife across large parts of the country (Photo: Pankaj Sekhsaria)

Saturday, October 10, 2009

The 2nd Class Citizen

The second class citizen

5 October 2009

Pankaj Sekhsaria

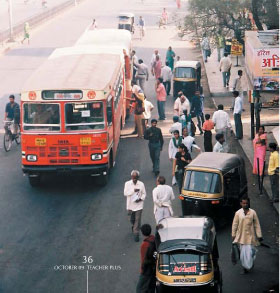

There is a new hierarchy that has slowly but surely entrenched itself in India’s urban reality. It is not really articulated in that light, but it is an experience that any resident of our cities could not have missed. Get on to the roads of your city as a pedestrian or a cyclist and you know instantly that you are a second class citizen. Zooming cars and two-wheelers, blaring horns, billowing smoke, narrower footpaths, fewer trees – it is increasingly a punishment to get out on to the city roads if you don’t have a personalised mode of motor transport.

More vehicles on our roads

Vehicles are being added to city roads like there is no tomorrow and the introduction of newer and cheaper cars like TATA’s Nano is only going to add to the unyielding rush. While the average human population in six of our biggest metros increased by a factor 1.8 between 1981 and 2001, vehicle numbers increased by over six times. Last year, Bangalore recorded the highest vehicle growth rate in the country with 14 per cent against a national average of 10, and 1000 cars are being added to the roads of New Delhi every day. A crisis awaits us around the corner, if it is not upon us already.

Unfortunately, all solutions suggested to deal with the growing problems of congested roads and traffic bottlenecks are only short sighted band-aids on the symptom. We have lost complete sight of the disease and the drug that we are providing is only adding fuel to the fire. The problem, we need to realise, is not a shortage of road space or width but the astronomically growing number of vehicles.

While no effort is being made to reduce these, huge investments continue to be thrust into creating more infrastructure as a mindless clamour for even more, out-shouts all other voices and suggestions of saner solutions. While there is some recognition now of the need for better public transport systems, the focus continues to be on the hugely capital intensive metro rail systems like the one proposed in Bangalore and Hyderabad. This, even as existing metropolitan bus services continue to languish with little or no additional investment and a quality of service that can only be considered poor. The efficiency and the value of supporting and augmenting existing services is best illustrated by Mumbai’s Bombay Electric and Suburban Transport (BEST) service. The BEST, it is said, carries about 50 per cent of Mumbai’s total road users, yet occupies only 4 per cent of the city’s road space.

More roads is not the solution

In line with the logic that growth in vehicle population is non-negotiable and questioning it amounts to sacrilege, the single biggest activity in our cities in recent times has been road and flyover construction and road widening. Trees, footpaths, old shops, houses – nothing matters. Conservative estimates suggest, for instance, that in Pune alone, at least 50,000 trees have been chopped down in the last five years alone, many to accommodate the increasing traffic. Pedestrian and cyclists occupy minimum road space and cause no pollution at all, but that is of no consequence. By cutting trees and reducing (even eliminating) footpaths, the situation is only being made more hostile for them. An excellent example of this is the construction of grade separators and the huge expansion of road width on the highway in the suburbs of Pune where I live. While motorists are delighted for obvious reasons, others, particularly those who walk or use cycles have been completely forgotten. There are a number of sections in this stretch where one has to take a detour of at least a couple of kilometers to just cross over to the other side. Twenty minutes of driving time saved for a motorist has directly translated to at least twice the duration of travel time for a pedestrian. School children and old people, in fact, suffer the most.

The recently published nation-wide study on ‘Traffic and Transportation Policies and Strategies in Urban Areas in India’ that was commissioned by the Union Ministry for Urban Development provides some shocking statistics and evidence of this. Mumbai sees an unbelieveable 22,000 road accidents every year. Ten people on an average are killed every day in our metros in road accidents. Delhi tops the list with more than 2000 deaths per year followed by Hyderabad (1196 deaths) and Bangalore (833 deaths). Even smaller towns like Hubli-Dharwad report more than one death every alternate day in road accidents. The report points out, that a majority of the road accident victims are indeed pedestrians – something that is not difficult to understand when one sees that the percentage of roads with pedestrian footpaths is less than 30 per cent in most of our cities today.

A pedestrian first

We should remember that every citizen, even a vehicle owner, is also a pedestrian at some point in his or her use of the roads of a city. Unless priorities in urban planning, in the media and in our thinking are not refocused, this problem is bound to increase. Merely adding and widening roads is not going to help. What is needed is a more fundamental effort at improving public transport, reducing private vehicles and putting the welfare and safety of the pedestrian and cyclist at the very centre of all that we do.

Otherwise, average city traffic speed will continue to fall and yet, more pedestrians will continue to die. The most frightening part is that it could be any one of us, at any point of time.

The author is an independent journalist and photographer and is associated with the environmental action group, Kalpavriksh. He can be reached at psekhsaria@gmail.com.

Here are some ideas that would encourage your students to explore this topic further

- Let your students get a sense of the changes that have taken place in their localities. Have roads been widened near their homes? Have footpaths been removed or added? Have trees been cut for road widening? The students could talk to their parents, grand parents and other elders in the house to find out.

- It might be interesting to get your children to go to the Road Transport Authorities in their cities and find out the growth in the number of vehicles in their city over a period of time. Let them find out how many vehicles are being added to their city roads every year.

- Ask the students to do a comparative study of the road width, footpath laws, vehicle densities, etc. between India and other countries.

- Get the children to document the roads in the cities that have no footpaths today and observe the situation of cyclists and pedestrians. They could spend some time on the roadside, traffic junction and see how people behave.

- Doing an analysis of relative benefits of different modes of transport. How much space does a bus occupy and how many people does it carry? How does it compare to a car or a cycle?

Tuesday, October 6, 2009

'Scientific undertakings are political projects'

INTERVIEW

Politics of science

| Interview with Geert Somsen, a historian of science at Maastricht University. |

Geert Somsen at Jantar Mantar in New Delhi.

GEERT SOMSEN is a historian of science with the Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences at Maastricht University in the Netherlands. He currently directs his faculty’s Graduate School and teaches in several bachelor’s and master’s programmes. He graduated in Chemistry but switched to historical research about 20 years ago. Within this field, he has become increasingly interested in the status of science in general. How has science been characterised in the past? What have scientific approaches been meant to supplant? How has science figured in self-portrayals of the West as compared to ‘the rest’? A training in science and technology studies (STS), meanwhile, prevents him from taking the advertised image of science for the actual product.

Somsen discusses with Pankaj Sekhsaria, of the Pune-based Kalpavriksh Environment Action Group, his views on interdisciplinarity, his more recent work on ‘scientific internationalism’, ‘politically active’ scientists and his travel to India and Central Asia to look at old traditions of astronomy and science in these parts of the world. Excerpts from a free-ranging interview:

From an undergraduate degree in chemistry to a Ph.D. in the History of Science and finally into inter-disciplinary studies, your academic journey is quite an interesting one.

I graduated in 1992 in Chemistry but I had always liked subjects such as Science and Society, Philosophy of Science, and in the third year of graduation, we had History of Science which I really liked. I then did my Ph.D. in History of Science at the Institute for the History of Science in Utrecht [in the Netherlands] and there was a huge mental transformation from being a natural scientist to being a historian.

My interest in philosophical issues continued and I got more and more fascinated by constructivist approaches. So, during my Ph.D. I did an internship at the University of California, San Diego, in the United States. At that time they had what was called the Science Studies programme – an interdisciplinary graduate programme of history, philosophy and sociology of science. And they had all these stellar names then – Bruno Latour, Steven Shapin, and in philosophy Philip Kicher was there, Chandra Mukerji.... It was really exciting, especially when all these people got together every week in their colloquiums and the poor speakers were completely grilled [laughs]. They would fly in speakers from all over the country, sometimes from all over the world, so it was really great.

I then did a postdoc in Philadelphia, was in Cambridge in England for a while too, and then landed here in Maastricht. Our faculty is very interdisciplinary in research, but especially teaching, and I became even more interdisciplinary here. So I was a historian of science and an STS studies person even before I came, and here I also got involved in courses on avant-garde movements, political ideologies, on all sorts of things.

Do you look at yourself then as a historian or as a scientist?

Historian, definitely not a scientist. I mean, scientists study nature and STS people study science, right? So the object of study is different. People in STS, I think, are from the humanities and social sciences because the object of the study is what scientists do. What scientists do is study rabbits, stars and DNA [laughs] and that is very different. So, I was trained in that [science], and it helps to have some inside knowledge, but I had to sort of make a mental switch.

I also have that experience, then, of what it means to be a scientist. An anthropologist, for instance, needs to acquire some inside knowledge of the culture he is studying. Now, I come from that culture. I only have to step back and look at what scientists are doing. I think it is helpful because it makes me able to deal with more technical issues.Whereas, if I would have been trained in history, I wouldn’t have been able to study what chemists are talking about, because I wouldn’t understand it.

Would you agree that historical investigation is perhaps the best starting point for interdisciplinary and STS kind of work.

When you look at Thomas Kuhn, for example, I think that is certainly the case. He was a sort of a philosopher who was very interested in history and he had much more of a relativist look. It started for him with an appreciation that Aristotelian physics, which we regard as no longer valid, in itself is completely valid. It was a different way of looking at the world and that brought Kuhn to a sort of relativism, which then made him theorise about scientific change. That Kuhnian turn, then, has partly come out of history.

As a historian do you find yourself better placed to work in this field?

No, not really. I see myself on par with sociologists and anthropologists.

So there is no particular advantage that you bring because you are a historian?

Sure. History of science has its own advantage and I really like it. That doesn’t however mean that I am better at STS studies than sociologists or anthropologists are.

You do not feel privileged in any way of being a historian…?

No, but what I think it does is that it brings a sort of a relativism with it, which is a privilege. And that is what the historians have from the outset, but that then is also true of an anthropologist.

So what then are the biggest challenges and advantages of doing interdisciplinary work?

Well of course, it is always combining perspectives that is difficult, especially because they are not always compatible. But that’s when it is interesting. Take, for example, a philosopher’s and a historian’s perspective on how knowledge is produced. A philosopher will always tend to have some sort of a formalised, generalised account that is ideally true even if it is not how it works in practice, whereas, a historian or a sociologist or an anthropologist doesn’t care about how it should be.

It will be the specific thing that they are looking at …

Yes. So a major advantage [of interdisciplinarity] is that as a practitioner, especially if you come from one background, it makes you very aware of the limitations of your own perspective. It makes you aware that there are other perspectives that are also legitimate and interesting. If you are trained within only one discipline then there is a chance that you begin to believe that your perspective is the perspective of the world and this is the way it all is. It can become very parochial in a way and interdisciplinarity makes you lose that. It makes you a little more modest. I think it’s a good thing.

Science & IdeologyAnd what is the relevance of interdisciplinary and STS studies in today’s context?

I think I have an original answer here [laughs]. I totally agree that the relevance of STS is that it brings about a better understanding of the workings of science and technology. But there is also a cultural part and I think you don’t hear that very often but it is relevant – that science and technology also have an ideological importance.I can see it in my reading for the course I am teaching, the ‘Idea of Europe’, a sort of general history course.

Technology, particularly science, comes in often into this idea. Science has been an important component of the self-image of the West or of Europe or of the modern world, right? Why are we modern and why aren’t others? Historians and other people have pointed to democracy and things like freedoms, human rights, but most often it is because we have modern science, right? So, we’ve invented this sort of method or trick, or whatever it is, that made it possible for us to understand and control the natural world and nobody else has ever invented that. Now whether this is true or not is one question… what is more important is that this figures in several representations of the West to sort of legitimate a hierarchy between the West and other people.

I just read a quote by Henry Kissinger, the National Security Advisor of the U.S. during the Vietnam war. He says about the underdeveloped world: that they haven’t had the Newtonian revolution, so they never learnt to think in a scientific way; they can’t really understand things, so they need us to do it for them. I think this is very common since the Enlightenment – the idea that we have learnt how to think scientifically and they, whatever they is, haven’t. Therefore, justifying our dominant position in the world.

So there is a purpose to this deconstruction. Does one also have an end in mind when one seeks to deconstruct these ways of looking? Or is that not important?

Inside Ulugh Bek’s observatory in Samarkand, Uzbekistan, which is now a museum.

To what end? I think that’s a very good question. One answer would be exposure [laughs], showing that these are not inevitable truths but particular choices.

There is a lot of talk, ideological talk, about what science is and what science does, and like I said, about the superiority of the ways of the West. I think the relevance for STS people or for historians of science like me is to unravel this – to take away some Western arrogance and to undermine this argument of superiority – to make the public aware that all sorts of undertakings that claim to be scientific are in fact also political projects whether you like them or not.

For example, look at current psychology, which has become very mechanistic again. It is very much about cognitive science and brain research. Now I am not against that at all, but we need to keep in mind that this is not objective science but is very much based on a particular view of man, which is an ideological view. I think people need to be aware of that.

Can you tell us about your work on scientific internationalism…

A widespread idea is that science by its very nature is international, that scientists all over are doing, more or less, the same things and therefore form a global community – a republic of letters. Of course this is a very idealised view, because science and scientists, in fact, are just like anybody else.

Brigitte Schroeder Gudehus, for instance, has shown that after the First World War scientists were actually even more nationalist [laughs] than non-scientists. But what I am interested is not whether the idealised view is true or not, but how it is being used, how science as a champion of international cooperation is being mobilised ideologically. And you see that happening in various other ways too, for example in the pacifist movements around the 1900s that led to the establishment of the international court of arbitration in The Hague and later to the League of Nations and the United Nations. Science was held up as the sort of area where this had already happened, where there was already this kind of cooperation.

What I have found interesting is to see what this comes from. It’s from a particular group, the progressive liberals, who around 1900 were associated with the progressive movement in the U.S. that advanced this idea. Science was connected to another kind of internationalism during the Cold War. Gavin de Beer wrote this famous book called The Sciences Were Never At War. He is basically saying that nations have their battles, but scientists are always cooperating and he tries to show it historically.

His point, however, is a Cold War point that we should uphold these ideals of scientific internationalism because they are under attack. And who is attacking them? The Communists of course. So you see that these expressions of internationalism seem very lofty and great but you can unearth the politics behind it.

But then in this ideal form, is scientific internationalism achievable, is it desirable?

Yes, of course, it is desirable, but achievable, I am not so sure. It’s like what Gandhi said about Western civilisation – it would be a good idea [laughs]…. no, I’m less sceptical, – sure it’s desirable.

Then also your other work about politically active scientists…

Yes, this is the other thing that I have been looking at – the ideological uses of science mainly by left-wing scientists….

It is largely left-wing scientists?

Yes, it doesn’t need to be, but it is. The most famous politically active scientists were the so-called red professors in Cambridge in the 1930s – a lot of Communist scientists then, and they really took their Communism to their science. They said that in a capitalist society, science is used for the wrong ends and that we need to change this. We need to have much more planning of science so that it is used for the right ends, and we also need to use science in planning society so that we don’t leave questions of housing, food, etc., to the market mechanism but investigate and plan it scientifically. Well, that might be a nice idea, but there is also something scary about the planning. Critics say you are creating a total tyrannical regime and I think they were not completely wrong about that.

You have travelled to India too…

Yes, I have always been interested in non-Western science and its history. Most history of science is very Western-oriented. There is literature about other things, but it is on the fringe. I thought it would be nice to find out more about this, also to get a more balanced picture of development of science in the world.

We decided to look at astronomy because it is a sort of ubiquitous science – any civilisation has astronomy, if only because it needed to make a calendar and predictions and things. In Uzbekistan, we went to an observatory in Samarkand. It was created in the 15th century, used for a few years, and then gone. It was in the early 20th century that a Soviet archaeologist dug it up. It is a gigantic observatory, much bigger than anything in Europe at that time, and they could make very accurate measurements here. It was constructed by Ulugh Bek, the local ruler. His observations were very authoritative and also known in the West. And this was created in a civilisation, the Timurite empire, that I had never heard of before. Then we went to India... several observatories built, of course, by Jaisingh.

In Jaipur and Delhi…

Right. So this was a maharaja in the 18th century who built all these observatories, the best surviving ones are in Jaipur and Delhi. These are very interesting because first of all they are totally different from Western observatories, they look like skateboard tracks [laughs], they are very beautiful and second, they were built at a time that the standard in the West was telescopes – the telescopic observatory with a dome and a slit with a telescope.

Jaisingh knew this, he himself had a telescope, but he still built complete different ones, why? There was a question and what did he want? What was he trying to do? He spent loads of money on these things, as much on his palaces, which are enormous. I still can’t answer that question [laughs], but you realise that there are things in science going on there, all kinds of science for other means.

We talked actually to the current director of the observatory in Jaipur and he said that every year a Brahmin priest comes and draws a horoscope based on the measurements that they make. And I just bought one.

It’s called the ‘panchang’.

Oh, is that what it is?

But this also brings up the question of the interface of astrology with astronomy. There is an ongoing debate in India whether astrology is a science, and that it draws from astronomy.

But that’s also true for a lot of Western astronomy, that it was intimately connected with astrology, also during the times of modern science. You have to ask not just what was contributed by astronomers but also why were these observatories built? They cost a lot of money and usually they were built not by astronomers, but by some local ruler or state. What did they want? Well, to calculate dates and things like that – later they were for precision measurement for cartography and surveying purposes – for setting exact time and all that sort of stuff. But in the early modern period, astronomy was also very much used for astrology, to tell a king when to go to war, when to have an operation. So the combination of astronomy and astrology has been a common one, also in the West.

The point, however, is something I made earlier and I’d like to stress it again. It is not whether this use of science or that use is right. That is not at the crux of what I am looking at or am interested in. What interests me is to see and find out how science which is considered neutral and objective actually isn’t, and how all sorts of people use it to meet their agendas and serve different purposes. It’s extremely important that we be aware of this reality of science and its use, actually various uses.

Calling a claim scientific, and therefore apolitical, is a very political move in itself, and one that can lead to the exclusion of other points of view from the discussion. Now I am not saying that all points of view are always equally worthy of consideration, but the scientific ones often need a little unpacking, and their politics should not be obscured.

Tuesday, September 29, 2009

Protected Area Update - October 2009

News and Information from protected areas in India and South Asia

Vol. XV No. 5

October 2009 (No.81)

LIST OF CONTENTS

EDITORIAL

Do we want the cheetah back?

NEWS FROM INDIAN STATES

ASSAM

Habitat protection vital to save River Dolphin in the Brahmaputra

Study on implications of the Forest Rights Act around Nameri NP and

Sonai Rupai WLS

Opposition to proposal of gifting rhino horns

More stringent punishment for poaching in Assam

Opposition to eviction for expansion of the Kaziranga NP

GUJARAT

MoEF rejects proposed port at Poshitara adjoining the Gulf of Kutch

Marine NP

JHARKHAND

Mobile phones and flying squads to tackle man-elephant conflict

Mobile phones and flying squads to tackle man-elephant conflictKARNATAKA

NEAA rejects thermal power station close to Anshi-Dandeli TR

Night traffic banned through Bandipur NP

MADHYA PRADESH

Displaced fisherfolk ask for full fishing rights in Tawa reservoir in

Satpura TR

MAHARASHTRA

Rise in Giant squirrel population in Bhimashankar WLS

Rise in Giant squirrel population in Bhimashankar WLSForest Dept employees warn of strike

Large scale transfers; PAs left unprotected

MEGHALAYA

Land adjoining Balpakram NP reclaimed from illegal miners

ORISSA

223 tribal families to be shifted from Similipal TR

223 tribal families to be shifted from Similipal TRPUNJAB

Ranjit Sagar Dam reservoir to be declared a wildlife sanctuary

RAJASTHAN

Great Indian Bustard sighted in Tal Chappar Wildlife Sanctuary

TAMIL NADU

Animal census in Point Calimere WLS

UTTARAKHAND

SC abandons elevated corridor for elephants in Rajaji NP

SC abandons elevated corridor for elephants in Rajaji NPUTTAR PRADESH

Steering committee for tiger conservation

NATIONAL NEWS FROM INDIA

Proposal to re-introduce the cheetah to India

Report on Ecologically Sensitive Areas in India

Four PAs proposed for inclusion on UNESCO heritage list

SCB'S Distinguished Service Award to Dr Kamal Bawa

National Green Tribunal approved

CEE plans Hoolock gibbon conservation programme in NE

1st installment of CAMPA money for eight states; dissatisfaction with

amount of money being released

Centre sends teams to assess situation in eight tiger reserves

SOUTH ASIA

BANGLADESH

US, Germany pledge US $19 million for reforestation of Chunati WLS

NEPAL

121 breeding tigers counted in PAs in Nepal

UPCOMING

Great Himalayan Bird Count, Winter - 2009

Great Himalayan Bird Count, Winter - 2009International Conference on Wildlife & Biodiversity Conservation

World Tiger Summit in Ranthambore TR in 2010

Global Tiger Workshop in Kathmandu

Global Tiger Workshop in KathmanduCall for Papers: People and Protected Areas - India case studies

OPPORTUNITIES

Research position for project on Snow leopard phylogeography and

conservation

Research position for Population genetics of a montane bird in the

Western Ghats

Research positions on bio-resource ecology and climate change in the

Sikkim Himalayas

Diploma in International Wildlife Conservation Practice

Part time environment education work in Mumbai

IN THE SUPREME COURT

PRESS RELEASES

National Conference of Ministers of Environment and Forests, 18/08/09

Future of Conservation Network, 19/08/09

READERS WRITE

There are many areas where the feasibility of the re-introduction will have to be carefully studied and this is what the meeting has proposed should be done. But the question really is a more fundamental one. Why do we want the cheetah back? There seem to be two different answers to this. One it would seem, and the Minister for Environment and Forests, Mr. Jairam Ramesh too referred to that - is to regain a part of the lost glory and history of this country. The other, as has been pointed by some wildlife experts, is that the cheetah, like the tiger, is the apex species of the

grassland habitat and it?s presence would, both, indicate and ensure the health of this badly abused ecosystem.

Prima facie, the arguments seem valid, but if looked at carefully, both have serious problems. It is certainly important to realize that grassland habitats are extremely productive but undervalued and abused. There is no doubt they should be conserved but introducing the cheetah from Africa hardly seems to be the way to do that. There are far simpler and effective ways to do it if we have the common sense and political will for it. It is also an extremely unfortunate part of our history that this glorious animal was shot into extinction nearly six decades ago. What is a scarier reality is that many species of plants, birds and animals stand today on the verge of joining the cheetah into that void called extinction. Flagship programs - Project Tiger and Project Elephant, for instance, face serious challenges and some might even say that they are floundering. How prudent would it then be to get into something new without ensuring the success of what we already have on hand?

Rather than spending huge amounts of time, human resources, energy and money towards an 'esoteric' bringing back of the 'dead' the effort has to be concentrated on preventing it happening again - with other species. That would be a far more worthwhile and valuable endeavour. We can't undo the extinctions we have caused already. Let the fate of cheetah be a grim pointer to that reality.

---

PROTECTED AREA UPDATE

Vol. XV, No. 5, October 2009 (No. 81)

Editor: Pankaj Sekhsaria

Editorial Assistance: Reshma

Illustrations: Madhuvanti Anantharajan

Produced by: Kalpavriksh

Ideas, comments, news and information may please be sent to the

editorial address:

KALPAVRIKSH, Apartment 5, Shri Dutta Krupa, 908 Deccan Gymkhana, Pune

411004, Maharashtra, India. Tel/Fax: 020 ? 25654239.

Email: psekhsaria@gmail.com

Website: www.kalpavriksh.org

***

Publication of the PA Update Vol. XV, No. 5 has been supported by the

DULEEP MATHAI NATURE CONSERVATION TRUST, the FOUNDATION FOR ECOLOGICAL

SECURITY, GREENPEACE INDIA, the ROYAL SOCIETY FOR THE PROTECTION OF

BIRDS and the INDIAN BIRD CONSERVATION NETWORK

Tuesday, August 4, 2009

Citizen Science for Conservation

By

Pankaj Sekhsaria

THE HINDU SURVEY OF THE ENVIRONMENT - 2009

One of the biggest concerns about scientific research over the years has been its ‘inaccessibility to common people’ and often, the ivory tower disposition of the scientific community itself. Debates over the lack of accountability in scientific establishments and their general unwillingness to engage with the masses have been common. Admittedly, all scientific endeavours don’t lend themselves to easy explanations, but that does not mean that none do.

A WORLDWIDE PHENOMENON

The fields of ecology and conservation, in particular, have been those where common citizens have contributed significantly with their keen interest and passion for the subject of their interest, be it birds, butterflies or plants, the marine environment or migration studies. Excellent examples of this abound around the world. Thousands of citizens in the USA, for instance, have joined Project BudBurst, a national field campaign for citizen scientists designed to engage the public in the collection of important climate change data based on the timing of leafing and flowering of trees and flowers. Another one that has global reach is Earthdive. Developed in partnership with the United Nations Environment Programme - World Conservation Monitoring Centre UNEP-WCMC and marine biologists from all over the world, it has a unique database (Global Dive Log) into which divers (and snorkellers) log sightings of key indicator species and human induced pressures.

They are so widespread and prominent, particularly in the west, that these citizen science initiatives have themselves become subjects of scientific and academic scrutiny. The relevance of citizen science in residential areas, for instance, is the subject of a recent paper published in the journal Ecology and Society by scientists of the Cornell Lab of Ornithology. “Citizen science”, the paper says, “is a method of integrating public outreach and scientific data collection locally, regionally, and across large geographic scales. Combining the power of the Internet with a populace of trained citizen scientists,” the paper concludes, “can provide unprecedented opportunity to mobilize a community to address new environmental problems, almost like having the environmental equivalent of a “fire brigade” ready to act as the need arises.”

CITIZEN SCIENCE IN INDIA

One of the first such attempts of Citizen Science in India is the nearly two decades old Asian Waterfowl Census (AWC). As part of the effort hundreds of volunteers and enthusiasts visit wetlands across the subcontinents on pre-decided dates in the winter season to count and then report the number of individuals of each species of waterfowl that they encounter. It was a simple idea that gave a good sense of bird numbers and trends, particularly, in wetlands that were visited and monitored regularly by the volunteers. For long this appeared to be the only effort of its kind, but now others have also taken off.

MIGRANT WATCH

Demoiselle Cranes and some Northern Pintails in Rajasthan – The birds are prominent winter migrants to the Indian Subcontinent. (Pic by Pankaj Sekhsaria)

Demoiselle Cranes and some Northern Pintails in Rajasthan – The birds are prominent winter migrants to the Indian Subcontinent. (Pic by Pankaj Sekhsaria)One initiative that has caught on really well is MigrantWatch, a citizen science programme for bird migration housed in the National Centre for Biological Sciences (NCBS) in Bangalore and being executed with the help of Indian Birds, a journal published from Hyderabad. Over 700 amateurs, serious researchers and weekend enthusiasts from across the length and breadth of the country are already part of the effort that seeks to document, understand and analyse the phenomenon of bird migration. Over 2500 first sightings of over 170 species have been logged since August 2007 and inputs are pouring in with every passing day. “The data gathered over the years,” says Uttara Mendiratta, a co-ordinator of MigrantWatch, “will help us examine the effects of climate change on the timing of bird migration in the subcontinent.”

Bird studies, in fact, easily lend themselves to initiatives of this kind and some of the most significant contributions towards understanding birds in India have indeed come from the enthusiastic amateur. What is significant this time is that the program is well thought out, structured tightly, and like in the west, is using the internet as a critical tool to put everything together.

The team at NCBS is also currently preparing to launch an India version of Project BudBurst to monitor plant (mostly tree) flowering and fruiting with the help of volunteers in another effort to understand impacts of climate change.

“It is not uncommon,” explains Mendiratta, “to hear anecdotal references from various people that plants have now started to flower and fruit at unusual times of the year. Recent information, for instance, reflects some concern about the early flowering of Cassia fistula in Kerala as this could result in the unavailability of the flowers during the festive season in April. The project,” she continues, “will be able to confirm such changes over the years using simple data collected by the volunteers.”

Rosy starlings and a myna, Kutch, Gujarat. The starlings were in the first list of birds being studied as part of the MigrantWatch program (Pic: Pankaj Sekhsaria)

Rosy starlings and a myna, Kutch, Gujarat. The starlings were in the first list of birds being studied as part of the MigrantWatch program (Pic: Pankaj Sekhsaria)PTEROCOUNT

One of the other endeavors, that has been up and running for a while is Project PteroCount, a South Asian Bat Monitoring Project that seeks to form a wide network of volunteers to create a comprehensive database of the roosting sites of the Indian Flying Fox, one of the largest fruit bats in the world. Started in 2005, this program has a modest volunteer base of about 75 people who have been gathering population and roost information and trends from 14 states across the country and also in Nepal. Dr. Sanjay Molur of the Coimbatore based Zoo Outreach Organisation was played a key role in starting this initiative. “We have some interesting information,” he says, “that has been coming through. The program has also benefited students from Tamil Nadu and Karnataka to create a focus in studying these creatures. One PteroCount volunteer,” he continues, “has now registered for a PhD on bat studies and a veterinarian from Himachal has managed to get a set of her own friends interested in observing the bat roosts. And,” he adds, “we are also in the process of starting a similar initiative to study spiders.”

ELEPHANTS IN MEGHALAYA

Staff of the Samrakshan Trust in the field noting down GPS readings and other details of elephants sightings from village folk (Pic: Pankaj Sekhsaria)

Staff of the Samrakshan Trust in the field noting down GPS readings and other details of elephants sightings from village folk (Pic: Pankaj Sekhsaria)Another program that has yielded some noteworthy results is a little initiative tucked away in Meghalaya in the North Eastern corner of the country. This is a project of the Samrakshan Trust to involve local people in monitoring elephant movement in the South Garo Hills, which is part of the Garo Hills Elephant Reserve. It is considered to be one of the most significant elephant bearing areas in the country but little is known of elephant behaviour here. In a situation where the landscape is large, where human and financial resources are seriously limited, and the area extremely difficult to access, it makes perfect sense to involve the local community. The elephant monitoring project here has done just that. For about three years now, a network of local individuals situated in remote and dispersed villages has been trained to collect data on elephant presence and movement in a simple and structured manner. The data has just been put together and it has created for the first time a good overview picture of the elephants here; including aspects like herd size and the general direction and period of their movements. Additionally, the study has provided some important insights into other dimensions like crop raiding by the elephants. It is, perhaps the first crucial step in understanding and perhaps solving the escalating problem of human-elephant conflict, and for ensuring a better future for both, the local communities and the elephant.

These examples provide the proof that science need not be distant, that it can be made meaningful with and for people and it can still be just as exciting. Needless to say, the involvement of the local communities should not be restricted to only those situations where the going is tough or where getting data is difficult. “It is crucial,” the Samrakshan research team points out in the latest issue of the journal Current Trends in Tropical Biodiversity Research and Conservation, “that the monitoring exercise contributes to local understanding and empowerment, and not simply to the satisfaction of the scientists and planners. The monitoring and evaluation process needs to ensure that there is adequate feedback into the local information system and the data involved is of mutual importance to researchers and locals.”

Citizen Science for Conservation is only just starting in India, but it does look like it has been a good take off. There will, hopefully, be many more in the years to come!

Web links:

Project BudBurst: http://www.windows.ucar.edu/citizen_science/budburst/

Earthdive: www.earthdive.com

MigrantWatch: www.migrantwatch.in

Project PteroCount: http://www.pterocount.org/

Samrakshan Trust: http://www.samrakshan.org/meghalaya.htm

Sunday, July 26, 2009

Vanishing Futures

http://www.hindu.com/mag/2009/07/26/stories/2009072650120500.htm

The Hindu, July 26, 2009

Vanishing futures

PANKAJ SEKHSARIA

| It is a small consolation that the Jarawas have not been wiped out like the great Andamanese. |

“Those who forget history,” it is said, “are condemned to repeat it.” What happens, however, when you forget history, but condemn someone else for it? Where does responsibility lie then and, importantly, what happens to those who are so condemned? The chilling answer can be found if we look at the history and the present of the indigenous communities of the Andaman Islands. One word: “extinction”.

Retracing roots

The fate of the Great Andamanese is a classic case in point. In the mid-19th century when the British established the penal settlement in the Andamans, it was estimated that there were at least 5,000 members of the Great Andamanese community that was divided into 10 distinct language and territorial groups. In just a century and a half, the population has come down to a little more than 50; all herded onto the small Strait Island a short distance away from Port Blair.

The damage was mainly done in British times. In his 1899 classic A History of our Relations with the Andamanese, M.V. Portman, the British officer in charge of the Andamanese, describes in a bleak, unnerving record the impact of the 1877 epidemic of measles, the worst to hit the Great Andamanese.

…All the people on Rutland (Island) and Port Campbel are dead, and very few remain in the South Andaman and the Archipelago. The children do not survive in the very few births which do occur, and the present generation may be considered as the last of the aborigines of the Great Andaman…

The story of the Onge of Little Andaman Island is very similar. From nearly 700 in the 1901 census, their number has fallen to about 100 today. While a large part of their 730 sq. km. island home is still called the ‘Onge Tribal Reserve’ the protection is only on paper. The biggest violator, tragically, has been the Indian state that ruthlessly (and illegally) logged the forest home of the Onge for nearly three decades till the Supreme Court put a stop to it in 2002.

From late 1960s onwards, thousands of people from mainland India were sent to Little Andaman Island under a Government of India programme to ‘colonise’ it. From being complete masters of their traditional forests of Little Andaman, the Onges have become outsiders in just four decades. Only the Onge lived on this island in 1965. Today, for every Onge on Little Andaman, there are at least 200 people from outside and the equation is changing even as we read this.

In one of the most bizarre incidents in the islands, eight members of the community died and 16 more were hospitalised after consuming a mysterious liquid that was washed ashore in a jerry can near their Dugong Creek settlement in December 2008. The administration says that the Onge consumed the liquid believing it to be alcohol, but doubts persist. Six months have passed but nothing is known of the liquid or the post mortem reports. Maybe the Onge made a mistake, but the authorities too have shown no urgency in getting to the bottom of the matter. The colonising enterprise has been successful and the annihilated, as we all know, tell no tales. They have no history even.

The story of the Jarawas is complex but follows the same trajectory. Thousands of settlers have been moved into the forests of the Jarawas, huge areas of their traditional forest home turned into agricultural and horticultural fields and the Andaman Trunk Road (ATR) constructed through the heart of Jarawa forests. Over decades, the road became the main channel to remove precious timber from these forests and also the main vector in bringing a whole range of vices to the Jarawa: alcohol, tobacco, gutka, reportedly, even sexual exploitation.

The road has even facilitated a new kind of tourism: “Jarawa tourism” where visitors drive down the ATR hoping to ‘see’ the Jarawa, as if they were some kind of living exhibits in an open air museum. Traffic continues to ply on the road in spite of clear Supreme Court orders in 2002 to close it down. Two epidemics of measles have already hit the Jarawa in the last decade. It can only be a small consolation that they were not wiped out like the Great Andamanese a little more than a century ago.