Pankaj Sekhsaria

First Published : 27 Nov 2010 09:35:00 AM IST

http://expressbuzz.com/magazine/wildlife,-the-last-priority/225667.html

Wildlife sanctuaries and national parks (protected areas) have for many years been at the centre of India’s official efforts at protecting the country’s wilderness, wildlife and biological diversity. While there have been many successes, questions are now being asked if the exclusionary model of conservation that alienates local communities will be sustainable in the long run. There have been many instances of strong opposition by these local communities, to either the creation of protected areas or their expansion, for fear of eviction and a strict restriction on their rights that inevitably follows. The general impression is that governments and forest departments are always keen on expanding the protected area (PA) network and communities or those who speak on their behalf are the ones opposing these moves.

The picture on the ground, however, is a more complex one as illustrated by two very interesting recent cases — one from Uttarakhand, and another from Maharashtra. In both these cases it is the state machinery that is against the expansion (or creation) of protected areas for reasons that have nothing to do with interests of wildlife or of the local communities. An interesting parallel was seen more than a decade ago when the Himachal Pradesh Government denotified about 10 sq km of the Great Himalayan National Park on the pretext that local communities were being negatively impacted by the national park. The real reason was that the Parbati Hydel Project had been held up and the only way to get it through was to have the river valley excluded from within the boundaries of the PA.

Now, in Uttarakhand, the state government has opposed the recommendation of the Supreme Court appointed Central Empowered Committee (CEC) for the expansion of the Askot Wildlife Sanctuary for a similar reason. The CEC had recommended that the boundary of the sanctuary be re-drawn to exclude the 111 villages presently located inside. It also suggested that the area of the sanctuary which is 600 sq kms presently be increased to 2,200 sq kms. This, the state government has opposed on the grounds that the move will restrict their capacity to tap the high hydro-electric potential of the area.

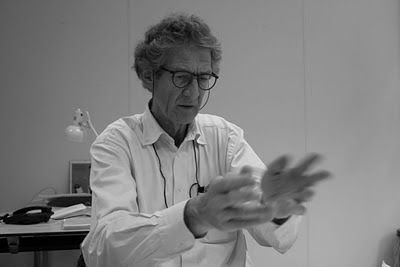

Askot Wildlife Sanctuary, Pic: E Theophilus

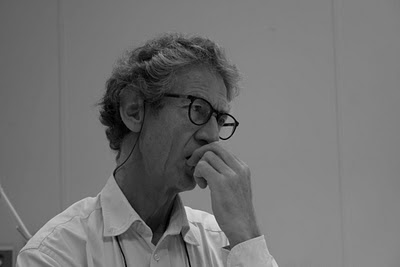

Bhagirathi Valley, Pic: E Theophilus

There are already 14 hydro-electric projects proposed within the existing sanctuary area and many more in the entire region. Local communities here have also been opposing the protected area, but then, they (at least some of them) have also vehemently opposed the spree of dam building that the region is likely to see. The recent cancellation of the Loharinag Pala Hydel Project and the decision to declare the Gomukh-Uttarakashi stretch of the River Bhagirathi as an eco-sensitive zone is just one outcome of this.

In Maharashtra, similarly, the long pending notification of the Mansinghdeo Wildlife Sanctuary is being held up because part of the land belongs to the Forest Development Corporation of Maharashtra. The Corporation which has logged these forests for timber has in the past opposed handing over the land for inclusion in the sanctuary and the decade old proposal continues to languish. In 2004, it had even moved an application before the High Court, arguing that it would lose nearly Rs 1,400 crores if the ban on timber logging was implemented in the 10 km radius of PAs, as suggested. The state has now suggested the reduction of the proposed 182 sq km to 143 sq km by leaving out the Mansinghdeo block after which the sanctuary was to be named. Experts have noted that the areas to be left out have some of the best forests and form an important corridor connecting the Nagzira Wildlife Sanctuary and the tiger reserves of Tadoba, Melghat and Pench.

Spotted deer in Tadoba Andhari Tiger Reserve. Pic: Pankaj Sekhsaria

The situation has been such that Environment and Forests Minister Jairam Ramesh had himself written to then Maharashtra Chief Minister Ashok Chavan, pressing for the notitification of the sanctuary.

These are situations we have encountered repeatedly over the years, with only minor variations in the script. A number of projects including those of mining, dam construction, laying of roads and railway lines and industrial activities have repeatedly been allowed by denotifying areas protected for wildlife. It is clear that in the present scheme of wildlife conservation and protected areas, local communities are the most dispensable entities. And in the present dominant paradigm of ‘development’ and primacy to commercial interests it is protected areas, wildlife and local people that are all together in being at the bottom of the list of priorities, if they find a place in that list at all.

There are different sets of people opposing wildlife conservation and protected areas for various reasons. It’s important to note that generally it is one set that has its way.

— The writer is an environmental researcher, writer and photographer. psekhsaria@gmail.com